Source of

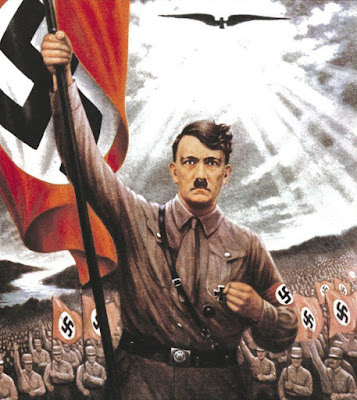

the text: How Hitler Consolidated Power

in Germany and Launched A Social Revolution by general

Leon Degrellé

„We have the power. Now our

gigantic work begins.“

Those were

Hitler’s words on the night of January 30, 1933, as cheering crowds surged past

him, for five long hours, beneath the windows of the Chancellery in Berlin.

His

political struggle had lasted 14 years. He himself was 43, that is, physically

and intellectually at the peak of his powers. He had won over millions of

Germans and organized them into Germany’s largest and most dynamic political

party, a party girded by a human rampart of hundreds of thousands of storm

troopers, three fourths of them members of the working class. He had been

extremely shrewd. All but toying with his adversaries, Hitler had, one after

another, vanquished them all.

Standing

there at the window, his arm raised to the delirious throng, he must have known

a feeling of triumph. But he seemed almost torpid, absorbed, as if lost in

another world.

It was a

world far removed from the delirium in the street, a world of 65 million

citizens who loved him or hated him, but all of whom, from that night on, had

become his responsibility. And as he knew - as almost all Germans knew at the

of January 1933 - that this was a crushing, an almost desperate responsibility.

Seventy

years later, few people understand the crisis Germany faced at that time.

Today, it’s easy to assume that Germans have always been well-fed and even

plump. But the Germans Hitler inherited were virtual skeletons.

During the

preceding years, a score of „democratic“ governments had come and gone, often

in utter confusion. Instead of alleviating the people’s misery, they had

increased it, due to their own instability: it was impossible for them to

pursue any given plan for more than a year or two. Germany had arrived at a

dead end. In just a few years there had been 224,000 suicides - a horrifying

figure, bespeaking a state of misery even more horrifying.

By the

beginning of 1933, the misery of the German people was virtually universal. At

least six million unemployed and hungry workers roamed aimlessly through the

streets, receiving a pitiful unemployment benefit of less than 42 marks per

month. Many of those out of work had families to feed, so that altogether some

20 million Germans, a third of the country’s population, were reduced to trying

to survive on about 40 pfennigs per person per day.

Unemployment

benefits, moreover, were limited to a period of six months. After that came

only the meager misery allowance dispensed by the welfare offices.

Notwithstanding

the gross inadequacy of this assistance, by trying to save the six million

unemployed from total destruction, even for just six months, both the state and

local branches of the German government saw themselves brought to ruin: in 1932

alone such aid had swallowed up four billion marks, 57 percent of the total tax

revenues of the federal government and the regional states. A good many German

municipalities were bankrupt.

Those still

lucky enough to have some kind of job were not much better off. Workers and

employees had taken a cut of 25 percent in their wages and salaries. Twenty-one

percent of them were earning between 100 and 250 marks per month; 69.2 percent

of them, in January of 1933, were being paid less than 1,200 marks annually. No

more than about 100,000 Germans, it was estimated, were able to live without

financial worries.

During the

three years before Hitler came to power, total earnings had fallen by more than

half, from 23 billion marks to 11 billion. The average per capita income had

dropped from 1,187 marks in 1929 to 627 marks, a scarcely tolerable level, in

1932. By January 1933, when Hitler took office, 90 percent of the German people

were destitute.

No one

escaped the strangling effects of the unemployment. The intellectuals were hit

as hard as the working class. Of the 135,000 university graduates, 60 percent

were without jobs. Only a tiny minority was receiving unemployment benefits.

„The others,“

wrote one foreign observer, Marcel Laloire (in his book New Germany), „are

dependent on their parents or are sleeping in flophouses. In the daytime they

can be seen on the boulevards of Berlin wearing signs on their backs to the

effect that they will accept any kind of work.“

But there

was no longer any kind of work.

The same

drastic fall-off had hit Germany’s cottage industry, which comprised some four

million workers. Its turnover had declined 55 percent, with total sales

plunging from 22 billion to 10 billion marks.

Hardest hit

of all were construction workers; 90 percent of them were unemployed.

Farmers,

too, had been ruined, crushed by losses amounting to 12 billion marks. Many had

been forced to mortgage their homes and their land. In 1932 just the interest

on the loans they had incurred due to the crash was equivalent to 20 percent of

the value of the agricultural production of the entire country. Those who were

no longer able to meet the interest payments saw their farms auctioned off in

legal proceedings: in the years 1931-1932, 17,157 farms - with a combined total

area of 462,485 hectares - were liquidated in this way.

The „democracy“

of Germany’s „Weimar Republic“ (1918 - 1933) had proven utterly ineffective in

addressing such flagrant wrongs as this impoverishment of millions of farm

workers, even though they were the nation’s most stable and hardest working

citizens. Plundered, dispossessed, abandoned: small wonder they heeded Hitler’s

call.

Their

situation on January 30, 1933, was tragic. Like the rest of Germany’s working

class, they had been betrayed by their political leaders, reduced to the

alternatives of miserable wages, paltry and uncertain benefit payments, or the

outright humiliation of begging.

Germany’s

industries, once renowned everywhere in the world, were no longer prosperous,

despite the millions of marks in gratuities that the financial magnates felt

obliged to pour into the coffers of the parties in power before each election

in order to secure their cooperation. For 14 years the well-blinkered

conservatives and Christian democrats of the political center had been feeding

at the trough just as greedily as their adversaries of the left.

Nor did the

bribing of the political parties make them any more capable of coping with the

exactions ordered by the Treaty of Versailles. France, in 1923, had effectively

seized Germany by the throat with her occupation of the Ruhr industrial region,

and in six months had brought the Weimar government to pitiable capitulation.

But then, disunited, despising one another, how could these political birds of

passage have offered resistance? In just a few months in 1923, seven German

governments came and went in swift succession. They had no choice but to submit

to the humiliation of Allied control, as well as to the separatist intrigues

fomented by Poincaré’s paid agents.

The

substantial tariffs imposed on the sale of German goods abroad had sharply

curtailed the nation’s ability to export her products. Under obligation to pay

gigantic sums to their conquerors, the Germans had paid out billions upon

billions. Then, bled dry, they were forced to seek recourse to enormous loans

from abroad, from the United States in particular.

This

indebtedness had completed their destruction and, in 1929, precipitated Germany

into a terrifying financial crisis.

The big

industrialists, for all their fat bribes to the politicians, now found

themselves impotent: their factories empty, their workers now living as virtual

vagrants, haggard of face, in the dismal nearby working-class districts.

Thousands of

German factories lay silent, their smokestacks like a forest of dead trees.

Many had gone under. Those which survived were operating on a limited basis.

Germany’s gross industrial production had fallen by half: from seven billion

marks in 1920 to three and a half billion in 1932.

The automobile

industry provides a perfect example. Germany’s production in 1932 was

proportionately only one twelfth that of the United States, and only one fourth

that of France: 682,376 cars in Germany (one for each 100 inhabitants) as

against 1,855,174 cars in France, even though the latter’s population was 20

million less than Germany’s.

Germany had

experienced a similar collapse in exports. Her trade surplus had fallen from

2.872 billion marks in 1931 to only 667 millions in 1932 - nearly a 75 percent

drop.

Overwhelmed

by the cessation of payments and the number of current accounts in the red,

even Germany’s central bank was disintegrating. Harried by demands for

repayment of the foreign loans, on the day of Hitler’s accession to power the

Reichsbank had in all only 83 million marks in foreign currency, 64 million of

which had already been committed for disbursement on the following day.

The

astronomical foreign debt, an amount exceeding that of the country’s total

exports for three years, was like a lead weight on the back of every German.

And there was no possibility of turning to Germany’s domestic financial

resources for a solution: banking activities had come virtually to a

standstill. That left only taxes.

Unfortunately,

tax revenues had also fallen sharply. From nine billion marks in 1930, total

revenue from taxes had fallen to 7.8 billion in 1931, and then to 6.65 billion

in 1932 (with unemployment payments alone taking four billion of that amount).

The

financial debt burden of regional and local authorities, amounting to billions,

had likewise accumulated at a fearful pace. Beset as they were by millions of

citizens in need, the municipalities alone owed 6.542 billion in 1928, an

amount that had increased to 11.295 billion by 1932. Of this total, 1.668

billion was owed in short-term loans.

Any hope of

paying off these deficits with new taxes was no longer even imaginable. Taxes

had already been increased 45 percent from 1925 to 1931. During the years

1931-1932, under Chancellor Brüning, a Germany of unemployed workers and

industrialists with half-dead factories had been hit with 23 „emergency“

decrees. This multiple overtaxing, moreover, had proven to be completely

useless, as the „International Bank of Payments“ had clearly foreseen. The

agency confirmed in a statement that the tax burden in Germany was already so

enormous that it could not be further increased.

And so, in

one pan of the financial scales: 19 billion in foreign debt plus the same

amount in domestic debt. In the other, the Reichsbank’s 83 million marks in

foreign currency. It was as if the average German, owing his banker a debt of

6,000 marks, had less than 14 marks in his pocket to pay it.

One

inevitable consequence of this ever-increasing misery and uncertainty about the

future was an abrupt decline in the birthrate. When your household savings are

wiped out, and when you fear even greater calamities in the days ahead, you do

not risk adding to the number of your dependents.

In those

days the birth rate was a reliable barometer of a country’s prosperity. A child

is a joy, unless you have nothing but a crust of bread to put in its little

hand. And that’s just the way it was with hundreds of thousands of German

families in 1932.

In 1905,

during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II, the birthrate had been 33.4 per one

thousand. In 1921 it was only 25.9, and in 1924 it was down to 15.1. By the of

1932, it had fallen to just 14.7 per one thousand.

It reached

that figure, moreover, thanks only to the higher birth rate in rural areas. In

the fifty largest cities of the Reich, there were more deaths than births. In

45 percent of working-class families, there were no births at all in the latter

years. The fall in the birthrate was most pronounced in Berlin, which had less

than one child per family and only 9.1 births per one thousand. Deaths exceeded

the number of new births by 60 percent.

In contrast

to the birthrate, politicians were flourishing as never before - about the only

thing in Germany that was in those disastrous times. From 1919 to 1932, Germany

had seen no less than 23 governments come and go, averaging a new one about

every seven months. As any sensible person realizes, such constant upheaval in

a country’s political leadership negates its power and authority. No one would

imagine that any effective work could be carried out in a typical industrial

enterprise if the board of directors, the management, management methods, and

key personnel were all replaced every eight months. Failure would be certain.

Yet the

Reich wasn’t a factory of 100 or 200 workers, but a nation of 65 million

citizens crushed under the imposed burdens of the Treaty of Versailles, by

industrial stagnation, by frightful unemployment, and by a gut-wrenching misery

shared by the entire people.

The many

cabinet ministers who followed each other in swift succession for thirteen

years - due to petty parliamentary squabbles, partisan demands, and personal

ambitions - were unable to achieve anything other than the certain collapse of

their chaotic regime of rival parties.

Germany’s

situation was further aggravated by the unrestrained competition of the 25

regional states, which split up governmental authority into units often in

direct opposition to Berlin, thereby incessantly sabotaging what limited power

the central Reich government had at that time.

Even at the

beginning of the First World War (1914-1918), the German Reich included four

distinct kingdoms (Prussia, Bavaria, Wurttemberg and Saxony), each with its own

sovereign, army, flag, titles of nobility, and Great Cross in particolored

enamel. In addition, there were six grand duchies, five duchies, seven

principalities, and three free cities.

Each

regional state had its own separate government with parliament, prime minister

and cabinet. Altogether they presented a lineup of 59 ministers who, added to

the eleven Reich ministers and the 42 senators of the Free Cities, gave the

Germans a collection of 112 ministers, each of whom viewed the other with a

jaundiced eye at best.

In addition,

there were between two and three thousand deputies - representing dozens of

rival political parties - in the legislatures of the Reich, the 22 states and

the three Free Cities.

In the

Reichstag elections of November 1932 - held just months before Hitler become

Chancellor - there were no less than 37 different political parties competing,

with a total of 7,000 candidates (14 of them by proxy), all of them frantically

seeking a piece of the parliamentary pie. It was most strange: the more

discredited the party system became, the more democratic champions there were

to be seen gesturing and jostling in their eagerness to climb aboard the gravy

train.

Honest,

dishonest, or piratical, these 112 cabinet ministers and thousands of

legislative deputies had converted Germany into a country that was

ungovernable. It is incontestable that, by January of 1933, the „system“

politicians had become completely discredited. Their successors would inherit a

country in economic, social and political ruins.

Today, more

than half a century later, in an era when so many are living in abundance, it

is hard to believe that the Germany of January 1933 had fallen so low. But for

anyone who studies the archives and the relevant documents of that time, there

can be no doubt. Not a single figure cited here is invented. By January 1933,

Germany was down and bleeding to death.

All the

previous chancellors who had undertaken to get Germany back on her feet - including

Brüning, Papen and Shleiher - had failed. Only a genius or, as some believed, a

madman, could revive a nation that had fallen into such a state of complete

disarray.

When

President Franklin Roosevelt was called upon at that same time to resolve a

similar crisis in the United States, he had at his disposal immense reserves of

gold. Hitler, standing silently at the chancellery window on that evening of

January 30, 1933, knew that, on the contrary, his nation’s treasury was empty.

No great benefactor would appear to help him out. The elderly Reich President,

Paul von Hindenburg, had given him a work sheet of appalling figures of

indebtedness.

Hitler knew

that he would be starting from zero. From less than zero. But he was also

confident of his strength of will to create Germany anew - politically,

socially, financially, and economically. Now legally and officially in power,

he was sure that he could quickly convert that cipher into a Germany more

powerful than ever before.

„It will be the pride of my life,“ Hitler said upon becoming Chancellor, „if

I can say at the end of my days that I won back the German worker and restored

him to his rightful place in the Reich.“ He meant that he intended not merely

to put men back to work, but to make sure that the worker acquired not just

rights, but prestige as well, within the national community.

The

objective, then, was far greater than merely sing six million unemployed back

to work. It was to achieve a total revolution.

„The people,“

Hitler declared, „were not put here on earth for the sake of the economy, and

the economy doesn’t exist for the sake of capital. On the contrary, capital is

meant to serve the economy, and the economy in turn to serve the people.“

The Social Revolution

It took

several years for a stable social structure to emerge from the French

Revolution. The Soviets needed even more time: five years after the Bolshevik

revolution of 1917, hundreds of thousands of Russians were still dying of

hunger and disease. In Germany, by contrast, the great machinery was in motion

within months, with organization and accomplishment quickly meshing together.

The single

task of constructing a national highway system that was without parallel in the

world might have occupied a government for years. First, the problem had to be

studied and assessed. Then, with due consideration for the needs of the

population and the economy, the highway system had to be carefully planned it

all its particulars.

As usual,

Hitler had been remarkably farsighted. The concrete highways would be 24 meters

in width. They would be spanned by hundreds of bridges and overpasses. To make

sure that the entire Autobahn network would be in harmony with the landscape, a

great deal of natural rock would be utilized. The artistically planned roadways

would come together and diverge as if they were large-scale works of art. The

necessary service stations and motor inns would be thoughtfully integrated into

the overall scheme, each facility built in harmony with the local landscape and

architectural style.

The original

plan called for 7,000 kilometers of roadway. This projection would later be

increased to 10,000, and then, after Austria was reunited with Germany, to

11,000 kilometers.

The

financial boldness equalled the technical vision. These expressways were toll

free, which seemed foolhardy to conservative financiers. But the savings in

time and labor, and the dramatic increase in traffic, brought increased tax

revenues, notably from gasoline.

Germany was

thus building for herself not only a vast highway network, but an avenue to

economic prosperity.

These

greatly expanded transport facilities encouraged the development of hundreds of

new business enterprises along the new expressways. By eliminating congestion

on secondary roads, the new highways stimulated travel by hundreds of thousands

of tourists, and with it increased tourism commerce.

Even the

wages paid out to the men who built the Reichsautobahn network brought

considerable indirect benefits. First, they allowed a drastic cut in payments

of unemployment benefits, or 25 percent of the total paid in wages. Second, the

many workers employed in constructing the expressways - 100,000, and later

150,000 - spent much of the additional 75 percent, which in turn generated

increased tax revenues.

Hitler’s

plan to build thousands of low-cost homes also demanded a vast mobilization of

manpower. He had envisioned housing that would be attractive, cozy, and

affordable for millions of ordinary German working-class families. He had no

intention of continuing to tolerate, as his predecessors had, cramped, ugly „rabbit

warren“ housing for the German people. The great barracks-like housing projects

on the outskirts of factory towns, packed with cramped families, disgusted him.

The greater

part of the houses he would build were single story, detached dwellings, with

small yards where children could romp, wives could grow vegetable and flower

gardens, while the bread-winners could read their newspapers in peace after the

day’s work. These single-family homes were built to conform to the

architectural styles of the various German regions, retaining as much as

possible the charming local variants.

Wherever

there was no practical alternative to building large apartment complexes,

Hitler saw to it that the individual apartments were spacious, airy and

enhanced by surrounding lawns and gardens where the children could play safely.

The new

housing was, of course, built in conformity with the highest standards of

public health, a consideration notoriously neglected in previous working-class

projects.

Generous

loans, amortizable in ten years, were granted to newly married couples so they

could buy their own homes. At the birth of each child, a fourth of the debt was

cancelled. Four children, at the normal rate of a new arrival every two and a

half years, sufficed to cancel the entire loan debt.

Even before

the year 1933 had ended, Hitler had succeeded in building 202,119 housing

units. Within four years he would provide the German people with nearly a

million and a half (1,458,128) new dwellings!

Moreover,

workers would no longer be exploited as they had been. A month’s rent for a

worker could not exceed 26 marks, or about an eighth of the average wage then.

Employees with more substantial salaries paid monthly rents of up to 45 marks

maximum.

Equally

effective social measures were taken in behalf of farmers, who had the lowest

incomes. In 1933 alone 17,611 new farm houses were built, each of them surrounded

by a parcel of land one thousand square meters in size. Within three years,

Hitler would build 91,000 such farmhouses. The rental for such dwellings could

not legally exceed a modest share of the farmer’s income. This unprecedented

owment of land and housing was only one feature of a revolution that soon

dramatically improved the living standards of the Reich’s rural population.

The great

work of national construction rolled along. An additional 100,000 workers

quickly found employment in repairing the nation’s secondary roads. Many more

were hired to work on canals, dams, drainage and irrigation projects, helping

to make fertile some of nation’s most barren regions.

Everywhere

industry was hiring again, with some firms - like Krupp, IG Farben and the

large automobile manufacturers - taking on new workers on a very large scale.

As the country became more prosperous, car sales increased by more than 80,000

units in 1933 alone. Employment in the auto industry doubled. Germany was

gearing up for full production, with private industry leading the way.

The new

government lavished every assistance on the private sector, the chief factor in

employment as well as production. Hitler almost immediately made available 500

million marks in credits to private business.

This

start-up assistance given to German industry would repay itself many times

over. Soon enough, another two billion marks would be loaned to the most

enterprising companies. Nearly half would go into new wages and salaries,

saving the treasury an estimated three hundred million marks in unemployment

benefits. Added to the hundreds of millions in tax receipts spurred by the

business recovery, the state quickly recovered its investment, and more.

Hitler’s

entire economic policy would be based on the following equation: risk large

sums to undertake great public works and to spur the renewal and modernization

of industry, then later recover the billions invested through invisible and

painless tax revenues. It didn’t take long for Germany to see the results of

Hitler’s recovery formula.

Economic

recovery, as important as it was, nevertheless wasn’t Hitler’s only objective.

As he strived to restore full employment, Hitler never lost sight of his goal

of creating a organization powerful enough to stand up to capitalist owners and

managers, who had shown little concern for the health and welfare of the entire

national community.

One of the

first labor reforms to benefit the German workers was the establishment of

annual paid vacation. The Socialist French Popular Front, in 1936, would make a

show of having invented the concept of paid vacation, and stingily at that,

only one week per year. But Adolf Hitler originated the idea, and two or three

times as generously, from the first month of his coming to power in 1933.

Every factory

employee from then on would have the legal right to a paid vacation. Until

then, in Germany paid holidays where they applied at all did not exceed four or

five days, and nearly half the younger workers had no leave entitlement at all.

Hitler, on the other hand, favored the younger workers. Vacations were not

handed out blindly, and the youngest workers were granted time off more

generously. It was a humane action; a young person has more need of rest and

fresh air for the development of his strength and vigor just coming into

maturity. Basic vacation time was twelve days, and then from age 25 on it went

up to 18 days. After ten years with the company, workers got 21 days, three

times what the French socialists would grant the workers of their country in

1936.

These figures

may have been surpassed in the more than half a century since then, but in 1933

they far exceeded European norms. As for overtime hours, they no longer were

paid, as they were everywhere else in Europe at that time, at just the regular

hourly rate. The work day itself had been reduced to a tolerable norm of eight

hours, since the forty-hour week as well, in Europe, was first initiated by

Hitler. And beyond that legal limit, each additional hour had to be paid at a

considerably increased rate. As another innovation, work breaks were made

longer; two hours every day in order to let the worker relax and to make use of

the playing fields that the large industries were required to provide.

Dismissal of

an employee was no longer left as before the sole discretion of the employer.

In that era, workers’ rights to job security were non-existent. Hitler saw to

it that those rights were strictly spelled out. The employer had to announce

any dismissal four weeks in advance. The employee then had a period of up to

two months in which to lodge a protest. The dismissal could also be annulled by

the Honor of Work Tribunal. What was the Honor of Work Tribunal? Also called

the Tribunal of Social Honor, it was the third of the three great elements or

layers of protection and defense that were to the benefit of every German

worker. The first was the Council of Trust. The second was the Labor

Commission.

The Council

of Trust was charged with attending to the establishment and the development of

a real community spirit between management and labor. „In any business

enterprise“, the Reich law stated, „the employer and head of the enterprise,

the employees and workers, personnel of the enterprise, shall work jointly

towards the goal of the enterprise and the common good of the nation.“

Neither would

any longer be the victim of the other-not the worker facing the arbitrariness

of the employer nor the employer facing the blackmail of strikes for political

purposes. Article 35 of the Reich labor law stated that: „Every member of an

Aryan enterprise community shall assume the responsibilities required by his

position in the said common enterprise.“ In other words, at the head of the

company or the enterprise would be a living, breathing executive in charge, not

a moneybags with unconditional power. „The interest of the community may

require that an incapable or unworthy employer be relieved of his duties“

The employer

would no longer be inaccessible and all-powerful, authoritatively determining

the conditions of hiring and firing his staff. He, too, would be subject to the

workshop regulations, which he would have to respect, exactly as the least of

his employees. The law conferred honor and responsibility on the employer only

insofar as he merited it.

Every

business enterprise of 20 or more persons was to have its „Council of Trust“.

The two to ten members of this council would be chosen from among the staff by

the head of the enterprise. The ordinance of application of 10 March 1934 of

the above law further stated: „The staff shall be called upon to decide for or

against the established list in a secret vote, and all salaried employees,

including apprentices of 21 years of age or older, will take part in the vote.

Voting shall be done by putting a number before the names of the candidates in

order of preference, or by striking out certain names.“

In contrast

to the business councils of the preceding régime, the Council of Trust was no

longer an instrument of class, but one of teamwork of the classes, composed of

delegates of the staff as well as the head of the enterprise. The one could no

longer act without the other. Compelled to coordinate their interests, though

formerly rivals, they would now cooperate to establish by mutual consent the

regulations which were to determine working conditions.

Every 30th of

April, on the eve of the great national labor holiday, council duties ceased

and the councils were renewed, pruning out conservatism or petrifaction and

cutting short the arrogance of dignitaries who might have thought themselves

beyond criticism.

It was up to

the enterprise itself to pay a salary to members of the Council of Trust, just

as if they were employed in the work area, and „to assume all costs resulting

from the regular fulfillment of the duties of the Council“.

The second

agency that would ensure the orderly development of the new German social

system was the institution of the „Workers’ Commissioners“. They would

essentially be conciliators and arbitrators. When gears were grinding, they

were the ones who would have to apply the grease. They would see to it that the

Councils of trust were functioning harmoniously to ensure that regulations of a

given business enterprise were being carried out to the letter.

They were

divided among 13 large districts covering the territory of the Reich. As

arbitrators they were not dependent upon either owners or workers. They had

total independence in the field. They were appointed by the state, which

represented both the interests of everyone in the enterprise and the interests

of society at large.

In order that

their decisions should never be unfounded or arbitrary, they had to rely on the

advice of a „Consulting Council of Experts“ which consisted of 18 members

selected from various sections of the economy in a representation of sorts of

the interests of each territorial district.

To ensure

still further the objectivity of their arbitration decisions, a third agency

was superimposed on the Councils of Trust and the 13 Commissioners, the

Tribunal of Social Honor.

Thus from

1933 on, the German worker had a system of justice at his disposal that was

created especially for him and would adjudicate all grave infractions of the

social duties based on the idea of the Aryan enterprise community. Examples of

these violations of social honor are cases where the employer, abusing his

power, displayed ill will towards his staff or impugned the honor of his

subordinates, cases where staff members threatened work harmony by spiteful

agitation; the publication by members of the Council of confidential information

regarding the enterprise which they became cognizant of in the course of

discharging their duties. Thirteen „Tribunes of Social Honor“ were established,

corresponding with the thirteen commissions.

The presiding

judge was not a fanatic; he was a career judge who rose above disputes.

Meanwhile the enterprise involved was not left out of the proceedings; the

judge was seconded by two assistant judges, one representing the management,

another a member of the Council of Trust.

This

tribunal, the same as any other court of law, had the means of enforcing its

decisions. But there were nuances. Decisions could be limited in mild cases to

a remonstrance. They could also hit the guilty party with fines of up to 10,000

marks. Other very special sanctions were provided for that were precisely

adapted to the social circumstances; change of employment, dismissal of the

head of the enterprise or his agent who had failed in his duty. In case of a

contested decision, the legal dispute could always be taken up to a Supreme

Court seated in Berlin-a fourth level of protection.

This was only

the end of 1933, and already the first effects could be felt. The factories and

shops large and small were reformed or transformed in conformity with the

strictest standards of cleanliness and hygiene; the interior areas, so often

dilapidated, opened to light; playing fields constructed; rest areas made

available where one could converse at one’s ease and relax during rest periods;

employee cafeterias; proper dressing rooms.

With time,

that is to say in three years, those achievements would take on dimensions

never before imagined; more than 2,000 factories refitted and beautified;

23,000 work premises modernized; 800 buildings designed exclusively for

meetings; 1,200 playing fields; 13,000 sanitary facilities with running water;

17,000 cafeterias. Eight hundred departmental inspectors and 17,300 local

inspectors would foster and closely and continuously supervise these renovations

and installations.

The large

industrial establishments moreover had been given the obligation of preparing

areas not only suitable for sports activities of all minds, but provided with

swimming pools as well. Germany had come a long way from the sinks for washing

one’s face and the dead tired workers, grown old before their time, crammed

into squalid courtyards during work breaks.

In order to

ensure the natural development of the working class, physical education courses

were instituted for the younger workers; 8,000 such were organized. Technical

training would be equally emphasized, with the creation of hundreds of work

schools, technical courses and examinations of professional competence, and

competitive examinations for the best workers for which large prizes were

awarded.

To rejuvenate

young and old alike, Hitler ordered that a gigantic vacation organization for

workers be set up. Hundreds of thousands of workers would be able every summer

to relax on and at the sea. Magnificent cruise ships would be built. Special

trains would carry vacationers to the mountains and to the seashore. The

locomotives that hauled the innumerable worker-tourists in just a few years of

travel in Germany would log a distance equivalent to fifty-four times around

the world!

The cost of

these popular excursions was nearly insignificant, thanks to greatly reduced

rates authorized by the Reichsbank.

The National Labor Service

Hitler

created the National Labor Service not only to alleviate unemployment, but to

bring together, in absolute equality, and in the same uniform, both the sons of

millionaires and the sons of the poorest families for several months’ common

labor and living.

All

performed the same work, all were subject to the same discipline; they enjoyed

the same pleasures and benefited from the same physical and moral development.

At the same construction sites and in the same barracks, Germans became

conscious of what they had in common, grew to understand one another, and

discarded their old prejudices of class and caste.

After a

hitch in the National Labor Service, a young worker knew that the rich man’s

son was not a pampered monster, while the young lad of wealthy family knew that

the worker’s son had no less honor than a nobleman or an heir to riches; they

had lived and worked together as comrades. Social hatred was vanishing, and a

socially united people was being born.

From the

first months of 1933, his accomplishments were public fact, for all to see.

Before end of the year, unemployment in Germany had fallen from more than

6,000,000 to 3,374,000. Thus, 2,627,000 jobs had been created since the

previous February, when Hitler began his „gigantic task!“ A simple question:

Who in Europe ever achieved similar results in so short a time?

Not without

reason were the swastika banners waving proudly throughout the working-class

districts where, just a year ago, they had been unceremoniously torn down.